Ravenseed: Chapter Three

In the Dark Ages, two knights and their squires riding to war encounter a monk who gives them an alarming warning

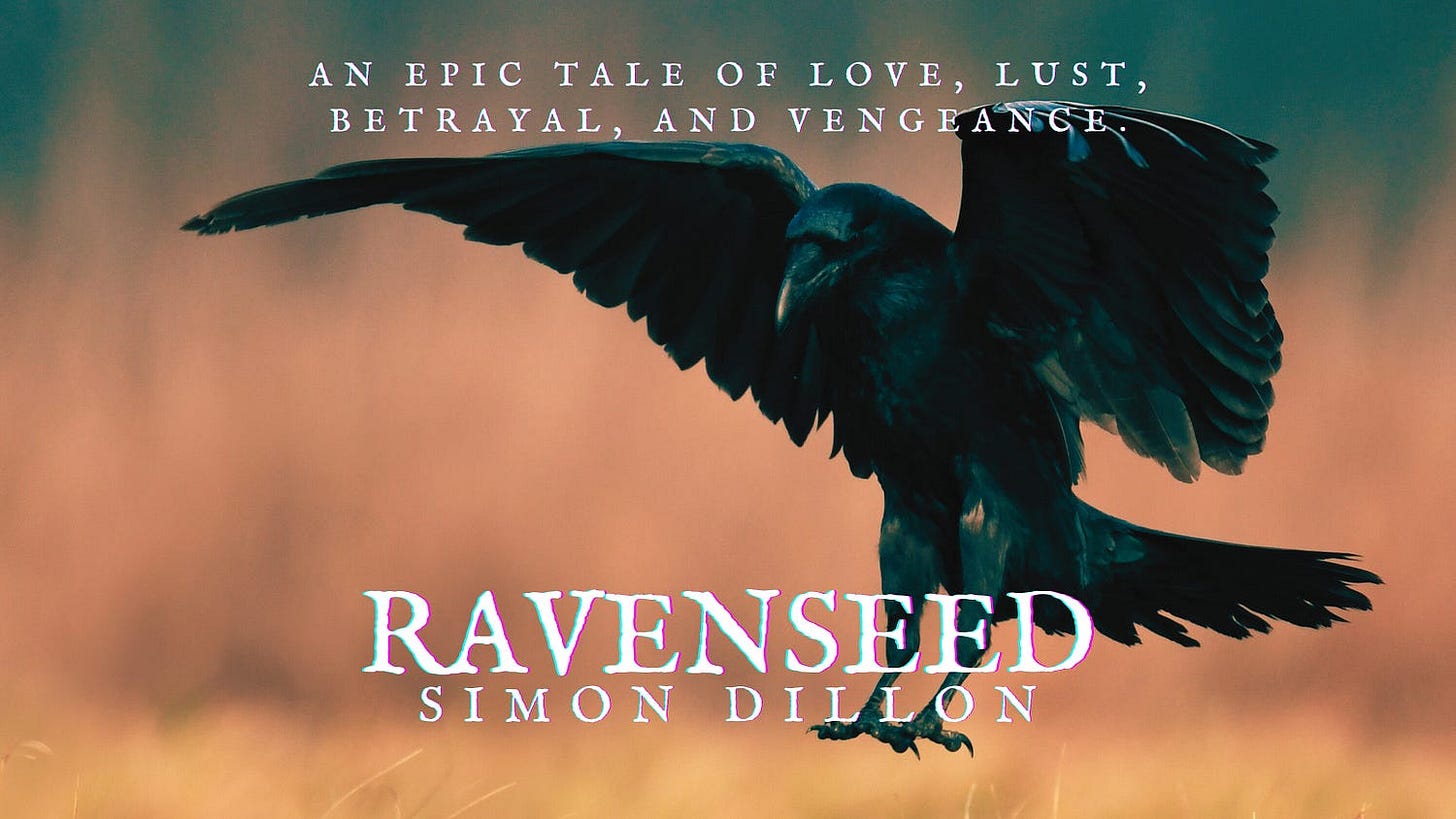

I’m currently showcasing the first four chapters of my newly released fantasy novel, Ravenseed. An epic tale of love, lust, betrayal, and vengeance, it opens in the present day, but the bulk of the narrative occurs in the Dark Ages. This chapter begins the Dark Ages segment of the story, and can be read in isolation as a taster for the entire novel. Alternatively, paid subscribers can read the previous chapters by clicking the links below.

Previous Chapters:

Click here for Chapter One: The Masked Traveller

Click here for Chapter Two: Rare Books

Chapter Three: The Monk’s Warning

Anglia, 532 AD.

I write this account mainly to get the matter straight in my own mind. Perhaps the reader will not understand or believe, but I must set in order the extraordinary events that scarred the last years of my life as a knight of the realm, lest fact and fiction conflict in my consciousness and madness take me.

It was not by choice that I took to the road with Sir Matthew Thorne, and our respective squires, Robin and Hugh. I thought our fighting days were over. Only when we received the summons from the King did we begin our fateful journey. Even then, we both considered ignoring the summons. We devised all manner of potential excuses — everything from the messenger miscarrying to illness, or being waylaid in some deed of apparent nobility that would appease the King’s wrath. His rather sanctimonious nature could be appealed to by the performance of alleged good deeds. He was also inclined to trust in his own legend. Perhaps he really did believe he had brought peace and stability to the land.

Said peace and stability seemed absent in the south-west. A rebellion in Cornwall led by Lord Rehnquist had the people in that region astir, demanding independence from the King. Such revolts were ruthlessly suppressed, and Sir Matthew and I had oft been involved in such suppressions. However, Lord Rehnquist had more than just a peasant rabble under his command. A great company of knights had defected to him, and he had hired or conscripted an army of some thousands. Therefore, the King recalled all loyal knights to join him at the muster in the fields just south of Camelford, near to where Lord Rehnquist and his troops were under siege at Camelford Castle.

So it was that Sir Matthew and I were forced back into service. We had both settled in Bovey Tracey near Exeter, working on the estate of Lord Philip Waldergrave. Sir Matthew had yet to take a wife, but I had become engaged to Julia, one of Waldergrave’s younger daughters. The arrangement had been mutually beneficial to all, since Waldergrave wished to provide additional inducement to retain my services.

Needless to say, the summons of the King proved upsetting. Waldergrave and Julia both feared I might not return, which was, of course, entirely possible. However, having survived several battles, I must confess my initial feeling at being recalled for duty to have been one of irritation. The journey from Bovey Tracey to Camelford would take at least two days, by which point the battle might have already been fought. Besides, as Sir Matthew and I both knew, the summons had come not because either of us were particularly sought after as great fighters, but because we were conveniently located, and would doubtless be considered good potential pawns, useful in dangerous attacks, and entirely disposable.

Whilst riding along a muddy track that ran across the southern ridges of Dartmoor on the route to Camelford, I surveyed the grim faces of our party. The countenances of Robin and Hugh were particularly downcast, as they had been forced to pack in a hurry. Their grey palfreys, Acorn and Nero, were laden with helmets, armour, and swords, as for the present we were riding relatively light in leather and hauberks. Our gear of war had seen better days, and the signs of inevitable wear perhaps reflected our inward state as well. Doubtless, our appearance would raise the odd contemptuous eyebrow among our more moneyed and aristocratic kin, but at least our horses were of good quality, bred specially for knights in Lord Waldergrave’s service. My own trusty steed, Trojan, was a white stallion fit for a king.

From his steed Apollo, a great black stallion, Matthew expounded upon our irksome predicament.

‘The King has always had his favourites. They all live in luxury at his castle, taking counsel together, yet we are never summoned to their deliberations.’

‘It’s no good getting upset about it,’ I said. ‘Our counsel has never been valued by land-owning knights, and never will be, I daresay.’

‘What would your counsel be now, Sir Peter Heath?’

I was well used to the mocking sneers of my companion and laughed. ‘My counsel is to find a good cause that requires our immediate attention, and thus delay our arrival at the field of battle, so as to hope that there is no longer a field of battle when we reach Camelford.’

Matthew laughed. ‘You mean a quest? The King will only approve if it is suitably noble. Are there no local maidens whose virginity is threatened by marauding invaders from across the seas?’

Matthew looked to our squires, both of whom appeared to give the matter mocking consideration. They were used to our cynical exchanges. I confess we did not set them a good example.

‘No one in this region sir,’ said Robin.

‘Robin made sure of that,’ said Hugh.

I could not help smirking at the bawdy humour of our young teenage squires. ‘Any party of marauding invaders would have to be small, for our fiction to retain credibility. Knights we may be, but we could not fight too many ravaging marauders.’

‘I seem to recall you were capable of holding off great numbers during the Battle of Bodmin,’ said Matthew.

‘Nonsense. I would have died if it weren’t for you stepping in to rescue me from my own foolhardiness.’

‘You were brave. I saw that, even if the King did not.’

‘I owe you my life. I won’t ever forget it.’

Matthew shook his head. ‘I’m not that man anymore. I’m not a hero.’

‘Nor am I. But even though your valour went largely unsung by the King and his court, I am profoundly grateful to still be breathing on account of you.’

‘Good sir knight, you move me deeply,’ said Matthew. His tone contained hints of bitter jest, but he could not hide being pleased that I at least recognised his courage and valued his friendship.

For several minutes we rode in silence. The moors were veiled with a grey mist and thin drizzle. We passed through rolling hills of grass and heather punctuated by granite tors that stood as silent, indifferent witnesses to our reluctant journey. I shivered. Although it was almost April, damp, bitter winter refused to yield its grip. I longed for warmer weather, but with battle just two days ride away, it was possible none of us would see it again.

‘Of course, we could visit the Raven Inn,’ I suggested, raising an eyebrow, and glancing in Matthew’s direction. ‘You’ve been there a lot lately. What’s the big secret?’

‘The Raven Inn is too far out of our way,’ said Matthew. ‘All but next to Plymouth.’

‘Come now Sir Matthew, it is a detour we could easily undertake, and still arrive at Camelford in timely fashion of a sort.’

‘Well, Sir Peter, if it is a detour you seek, there are other inns we might frequent that lie more along our direct path to Camelford. I know of a half dozen dens of iniquity that would more than assuage whatever sordid wishes you might wish to privately indulge. I seem to recall you undertaking many such diversions, in the so-called golden days of the King’s wars.’

‘You speak of women?’

‘Of women, of drink, of gambling, and of many other indulgences.’

Matthew laughed. I could not help but join in his mirth, even though the joke was at my expense.

‘It is true, I have enjoyed the companionship of a few kindly, warm-hearted women in days gone by.’

‘They must have been kindly indeed, to put up with your foul stench after the distances we rode to war,’ Matthew said. ‘And by no reasonable accounting can the quantity of women you have laid with be described as few.’

Robin and Hugh attempted to suppress their mirth, but I laughed.

‘Very well, there have been many. But though you jest with me, Sir Matthew, I can assure you that these days I am a changed man. I intend to be virtuous from this day forward, in view of my impending union with Julia.’

Matthew grinned. ‘Sir Peter a man of virtue? Is such a change possible? A part of me hopes not, for what amusement could I then glean from my oldest friend?’

‘Perhaps we are both set to become men of virtue. For one thing, you have yet to answer my enquiry as to why the Raven Inn holds such attraction for you, and why of late you have oft frequented that establishment. Could it be that at last you have discovered the pleasures of female companionship?’

‘Your guess indeed falls close to the mark, for I have recently met there a woman. The innkeeper’s daughter, in point of fact.’

I laughed. ‘Now it makes sense. What is the name of the unfortunate wench?’

‘Elizabeth.’

‘She must be special indeed for you to make such frequent and tiresome journeys, in all weathers. Oh, your absence has been noted. Waldergrave and I are no fools.’

‘She is a remarkable woman,’ said Matthew. ‘I intend to marry her.’

‘I confess to being intrigued. Sir Matthew, I would be fascinated to make her acquaintance. If you are indeed bound for battle and possible death, it would not do for there to be no farewell. We shall make the diversion to the Raven Inn and lodge there for one night at the minimum. You shall thence summon a local priest and marry Elizabeth. It is the least we can do. Should he enquire, the King will understand, for he will see such action as honourable.’

Matthew shook his head. ‘He will simply ask why I put Elizabeth before his summons.’

‘Let us speak honestly of this matter. None of us wish to ride to Camelford. You can simply say you were too ill to travel for a couple of days, and that you came as soon as you could. That way we can spend a day, two days, or perhaps even longer at the Raven Inn. What say you, Matthew? Shall we visit the fair maiden who stole your heart?’

‘Your reasoning is sound,’ said Matthew. ‘Yet I still feel our sense of duty to the King should be…’

‘Oh, hang the King! He’s too caught up in his own myth to give thought to the likes of us. We who have sacrificed so much, who have risked our lives time and again in the name of his absurd quests and wars, are owed this little indulgence. Should it transpire thus that we arrive once battle is done, we shall have no regret.’

‘I agree. And yet I fear our course is dishonourable.’

‘What if it is? Who shall know?’

‘There are other powers, besides we who dwell in the physical realm, who note the actions of mortal men.’

I laughed. ‘What gods could possibly care about two knights so oft overlooked by those for whom they fight? Behold, your good lady waits at the Raven Inn, and you should pay her the courtesy of regretfully informing her that you might not see her again.’

‘I am uncertain about the wisdom of such a journey.’

‘Hugh, pray tell, have you beheld this maiden that managed to penetrate the iron-clad defences around your master’s heart?’

‘I have indeed sir.’

‘Is she as remarkable as your master claims?’

‘She is quite beautiful sir.’

‘Did you witness the last parting of Elizabeth and your master?’

‘Yes sir.’

‘Can you expound on the nature of their parting?’

‘Well… Begging your pardon Sir Matthew, but Elizabeth was most sorrowful.’

I turned to Sir Matthew. ‘You see? She longs for a consummation in your relationship. Would you be cruel enough to deny that?’

‘If a priest can be found then yes, I will take Elizabeth as a wife. But there will be no consummation until that point. I will not dishonour her.’

‘Sir Matthew, it would seem you are much afflicted in this regard.’

‘Well Sir Peter, if you had ever been in love, you would understand.’

‘What are you talking about? I am in love. With Julia.’

Matthew laughed. ‘That is not the same. You are both mutually attracted and look to an expedient existence together. That is why I disbelieve your newfound declaration of virtue and marital fidelity.’

I scoffed. ‘Evidently, my feelings for Julia don’t match the deep, profound bond you feel with Elizabeth. But to the matter at hand, I still think we should stop off at the Raven Inn. What say you?’

Matthew sat brooding. Robin and Hugh exchanged knowing glances. The drizzle lifted for a brief moment, but a sharp gust of wind stung our faces. Sensing my serious-minded friend’s inward struggle, I indicated Trojan’s hooves.

‘My steed requires re-shoeing. The smithy did not have time to attend to Trojan before we left, but there is a smithy at the Raven Inn. Indeed, I hear no finer blacksmith works in these parts. It is only right and proper that we ride to war with our steeds properly prepared.’

Matthew laughed. ‘A fine pretext, Sir Peter. Nonetheless, we should not spend more than one night at the inn. I fear that my resolve will be sorely tested as it is, visiting Elizabeth on the eve of battle.’

I shrugged. ‘I must declare, Sir Matthew, in view of Hugh’s testimony regarding the subject of Elizabeth, that this detour is essential. If she is willing, and you both so desire one another, why not cast caution to the wind and take her? Even if we cannot find a priest to make it official, you may not get another opportunity.’

Matthew grinned. ‘You have argued your case most eloquently, and for that, I am grateful, old friend. So be it! We shall visit the Raven Inn, and you will meet Elizabeth.’

Following this exchange, we headed towards Plymouth. For a time, we continued through the peaks and valleys of the moors, before coming to a dense woodland. Amid the ashes, oaks, elms, and birches, I knew the path would eventually come to a fork, with a road that continued west on the right, and a path that branched off towards Plymouth, on the left.

The miles wore on, and although the rain had stopped, the wind picked up. Swirling, low cloud lingered, and a mist descended on the forest, clinging to the trees. The air still felt wet, despite the lack of rain, and every step our steeds took felt weary and reluctant. Moisture dripped from every overhanging branch and twig that lay along our path, and amid the muddy gloom I felt grateful that by the evening we would be resting in the warmth of the Raven Inn.

The path through the woods grew broader as we approached the fork in the road. To the left, the path went down into a valley, into thicker forest that I knew would eventually bring us to our destination, just outside Plymouth. To the right, the path climbed further, leading west towards the great river and the bridge that separated Cornwall from the rest of the land.

As we approached, I noticed a man in a brown robe standing facing us at the fork in the road. His face was hidden by a hood, but he appeared to be a monk. In his hand, he held a staff. Something about his manner bothered me, and it seemed clear that he wished to speak with us. Everyone else sensed the same, as we came to a joint decision to halt our horses.

‘Greetings friend,’ I said. ‘Can we help you?’

The Monk drew back his hood, revealing a youthful face with pale skin. His dark eyes were wide and intense. He looked us over, as though evaluating or assessing us. I didn’t care for his gaze, which felt uncomfortably shrewd and penetrating. It made me want to hide, though from what I did not know.

‘Are you lost?’ said Matthew.

‘I see my path better than you,’ said the Monk.

His voice had a curious, deep tone that echoed more than I expected amid the dense woodland. Was this really a monk from a local monastery? I shivered. Everything about this young man unsettled me. He didn’t belong in this landscape.

‘You speak in riddles,’ I said. ‘Yet we cannot break our journey to indulge in such discourse, as we wish to reach the Raven Inn by nightfall.’

‘So, you will turn left,’ said the Monk.

In his voice I sensed disappointment. I could not understand why our journey should be of interest to him, a complete stranger. What could he possibly know of our decision to take a detour to the inn, rather than continue west to Cornwall?

‘Who are you?’ I asked.

The Monk shook his head. ‘Who I am is unimportant, but you may call me Brother Mordecai.’

‘Well, Brother Mordecai,’ said Matthew. ‘If you do not require our assistance, we will wish you well and continue our journey.’

Mordecai addressed Matthew. ‘There is death ahead for you if you take the right path.’

Matthew and I exchanged bemused glances. This young monk was eccentric, possibly even mad, but he didn’t seem dangerous. Why then did he fill me with such unease?

‘Why are you saying that?’ asked Matthew.

‘Because something worse than death lies in wait if you take the left path.’

‘What if we turn around and go back the way we came?’ Matthew asked, not caring to hide the mockery in his voice.

The Monk did not answer. Matthew addressed him in exasperated tones. ‘Well, Brother Mordecai, we wish to avoid death, and I fail to see what could be worse than that, so if it’s all the same to you, I think we’ll continue on our journey to the Raven Inn.’

‘It is not all the same to me,’ said the Monk. ‘If you take the path to the Raven Inn, I will regret it. I am sent to deliver warnings, and when they are not heeded, I am grieved.’

‘Sent by whom?’ I asked.

The Monk did not answer. Robin and Hugh began to chuckle amongst themselves at this somewhat absurd figure. But there was a nervousness to their laughter, and however much we might have desired to ridicule Brother Mordecai, with hindsight I must admit that moment unsettled us all.

‘Brother Mordecai, you are not speaking reason,’ said Matthew. ‘You stand yonder, and make nebulous, mystical pronouncements, claiming we have a choice between death or something worse. That is no choice at all!’

‘If you do not understand that there are worse things than death, you have my pity.’ The Monk shook his head. ‘Perhaps I am destined to deliver warnings that are unheeded, so I better understand the perspective of God. But that is my burden to bear, not yours.’

The Monk sat down at the fork in the path and cast his eyes to the ground. Matthew and I stared at one another in bewilderment. What could this man know of our journey? How could he possibly think appearing here before us with no explanation, urging us to ride to certain death would possibly result in us heeding his advice? It was preposterous. Brother Mordecai had to be mad.

‘You’re insane,’ said Matthew, voicing my thoughts. He indicated to Hugh. ‘Come!’

We continued to ride, taking the left fork, onto the path that led down into the denser woodland. As we passed the Monk, he remained seated, staring down at the ground. Only as I turned my head from him did I catch, out of the corner of my eye, one final glance up at me. I couldn’t swear to it, but I sensed dismay, as though he had singled me out for special pity.

I felt bewildered at the Monk’s attitude. At the time I thought him mad, but even then, I couldn’t escape an inexplicable notion that our decision to turn left had been wrong. After riding a few yards, I turned back to where the Monk had been sitting. He had vanished.

The incident unsettled our group, although we did our best to hide the fact. Robin and Hugh began to mock what the Monk had said, and Matthew joined in with their jests. I contributed an occasional humorous remark, but they were half-hearted.

After a while, the talk died down and we rode on in silence. The light began to wane, and although the rain had stopped, and the skies had cleared, it felt colder. The journey seemed to pass more quickly than expected. Prior to the fork in the road, the footsteps of our steeds had seemed trudging and slow, yet now the pace picked up, through no particular urging of the riders. I couldn’t help but wonder if a hidden evil force now pushed us forward, urging us on to this supposed fate worse than death.

Our road took us deep into the forest, along the foot of a valley, up steeper wooded slopes, before emerging into farmland. We pass along paths through fields of wheat shoots and cattle, coming at length to the outlying huts and barns that constituted the outskirts of Plymouth. The path became a broader lane that entered another woodland, though less dense, with larger oaks and elms, spaced further apart. This lane zig-zagged upward, until eventually, it descended to a great river which we were able to ford, before riding up a little further, once again into more open country.

As we came to the long, straight stretch that led at last to the Raven Inn, we happened upon a traveller — another young man, perhaps but two or three years older than our squires, around eighteen or so. He had a shock of bright brown curly hair, dressed in a dark travelling cloak and leather boots. He rode a white mare and joined our road from a converging path to our left. The rider smiled and greeted us as we rode closer.

‘Greetings, sir knights,’ he said. ‘Might I ask, are you travelling to the inn up yonder?’

‘We are,’ said Matthew.

‘In that case, might I accompany you? I have had a long, weary journey, and been attacked by bandits. Mercifully I was able to escape their clutches, for I was on horseback, and they were not. Yet, I have had a frightening experience, and would take great comfort if I could be accompanied by honourable knights of the realm.’

I glanced back to Robin and saw him suppressing a smirk. I did not know why the young traveller amused him so, though I fancied my squire did not believe his tale. I decided to question him.

‘Why were you attacked?’

‘Oh… They wished to relieve me of my purse, as well as my horse.’

‘How many bandits were there?’

‘Four.’

I scrutinised the young man. There was something slightly frenzied about his expression, as if he were still experiencing the fear and thrill of being chased through the countryside by bandit thieves. Outwitting such a mob would no doubt have been frightening, but to emerge unscathed and regale knights of the realm with such a tale perhaps had made him feel a touch exhilarated.

Yet beyond this, I judged the young man to be more dangerous than he appeared. His eyes had a flicker of mischief, and I wondered as to his background.

‘What is your business?’ Matthew asked.

The young man patted a bag stashed behind his saddle, resulting in the unmistakable clink of coins. ‘I travel from place to place, playing games of chance. The Raven Inn is a fine establishment for such activity, and tonight I believe fortune shines upon me.’

Matthew laughed. It seemed we had fallen in with a scoundrel; perhaps the son of a nobleman, who had gone astray in a series of misadventures.

‘It is true that fine games of chance are played at the Raven,’ said Matthew.

‘Then perhaps you would care to join me, good sir?’

‘No thanks. I have other business at the inn. However, we are happy to ride in escort since our paths lie together. What is your name?’

The young man opened his mouth, and for a brief second, I got the impression he was about to use a name other than the one he finally spoke.

‘Tom,’ the young man replied eventually. ‘Tom Praeten.’

Matthew glanced at me. Clearly, he also believed there was more to Tom than met the eye but judged that the young traveller was not a threat.

‘Very well Tom Praeten, let us make haste for the inn.’

Chapter Four follows on Friday 14th June.

Copyright 2024 Simon Dillon. The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

This book seems to have several stories in one. It will be interesting to see how you finally make them converge.